The other day I wrote a longer piece about revisiting the topic of relaxation in Jiu-Jitsu.

If you didn’t get a chance to read it, I’d urge you to go back and read it. But here’s the upshot:

1. Everyone’s familiar with the advice to relax in training (we hear it, and often say it, all the time)

2. But just as there are levels in terms of technical execution (effectiveness), there are levels to relaxation (efficiency) as well, and these are less obvious or recognized

3. Even grapplers who are smooth, technical, and have excellent management of their physical energy could in almost all cases be even more relaxed –– rely less on their arms, grips, and hold less physical tension in their bodies –– and achieve results equal to, if not greater than, they currently experience

This takes a bit of honest evaluation and reframing for most of us who have been training for a long time and feel like we’re already pretty damned efficient and relaxed.

But what I’m talking about has nothing necessarily to do with “not spazzing”, “not muscling it”, or “not gassing out”.

Think of all those things as just Relaxation Level 1.

There’s a whole other level above that… let’s call it Level 2.

This is what Rickson referred to years ago after being asked about “Invisible Jiu-Jitsu,” where he described it as the difference between a “partial connection” and a “full connection.”

Relaxation is a key aspect of being able to achieve a “full connection” relative to an opponent.

Here was one of my epiphanies about this… A while back it dawned on me that my pressure top game was actually better when I was just lying on top of one of my students and talking through what we were working on to the class than it was when I was training live and trying to be heavy:

As in, even upper belt students who weigh 20 – 30 pounds more than me started gasping, groaning, and asking if I could put some weight back on the mat while I spoke to the class or they would have to tap out. Meanwhile, aside from my toes and balls of my feet on the mat, my body was completely relaxed.

Then I realized that when I was getting escaping pressure from those same opponents when we were drilling or rolling live, my body would slightly tense up, I’d begin relying much more on my arms to control and recover, and the time it took for them to reach that same “breaking point” would be much longer.

As I mentioned, I wasn’t doing anything egregious… I wasn’t squeezing hard, holding my breath, or fighting for all I was worth. It was just an unconscious level of excess tension in response to the increase in my training partners’ increasing resistance.

Not to mention, their frames, bumps, and bridges would have a much greater effect on me the more I tensed up.

That makes sense, right?

If you push or frame against a wooden plank, the entire plank moves. But if you push or frame against a sand bag, only the point of contact moves. And not only don’t you move the rest of the bag, the sand fills in the space around that point of contact and then becomes even harder to move!

Really focusing on proper body positioning while keeping constant mindfulness about relaxing has really been profound.

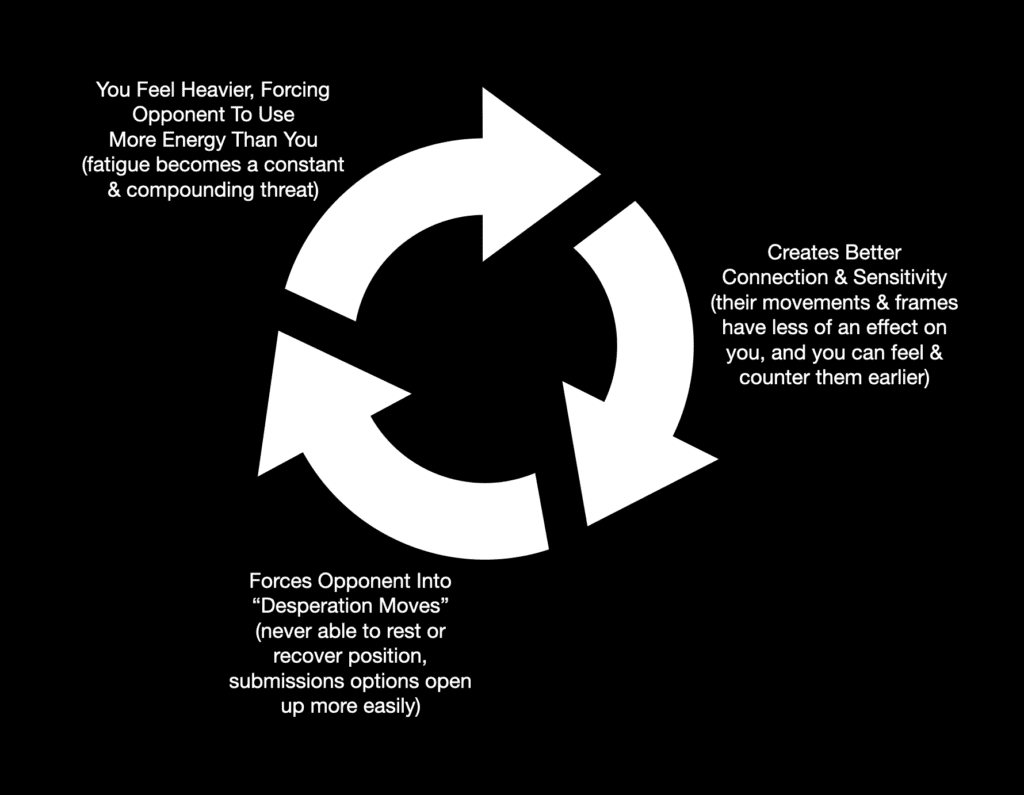

It truly allows you to create a virtuous Jiu-Jitsu Flywheel that optimizes for both efficiency and effectiveness. Here’s a visual of what that looks like:

The common response to this line of thinking is: “Great, but much easier said than done.”

Very understandable.

Here’s how to actually think about it and implement it so it’s not just a nice theory:

As counter-intuitive as it sounds, relaxation must be trained like a muscle or a skill, the difference being that it’s about removal rather than acquisition. Naturally when encountering force by way of an opponent’s resistance, our brain and body respond with force. Over time that must become more efficient and technical, but it’s almost always more than is necessary and we’re not even aware of it.

In order to develop greater relaxation, connection, and pressure, you have to take a step back in order to take several steps forward and create new feedback loops…

One of the hardest things I’ve noticed for both myself and others I’ve helped with this is that when you do it right you don’t feel like you’re doing anything, so your brain signals you to do more than you should. It’s deceptive.

But by slowing everything down a bit and having a chance to really talk to your training partners and study their reactions, you can begin to trust that feeling of “not doing anything”, recognize that it’s working, and eventually that will become your new default.

To train this, don’t just relying on full competitive rolling.

Do positional isolation training with your partners giving you progressive and adaptive resistance in just one spot at a time so you can make sure you’re both countering their escapes properly and staying as relaxed as possible at a lighter resistance level, then gradually have them dial it up.

Then start to layer in attacks following the same process.

The other way to do this is to practice on a less experienced training partner where you know that you can “lead the dance” and get quality reps in by essentially making the open roll an isolation training.

Trust me, it takes a while to develop but long term you’ll be incredibly thankful you put in the time and focus to add this invaluable asset into your game.