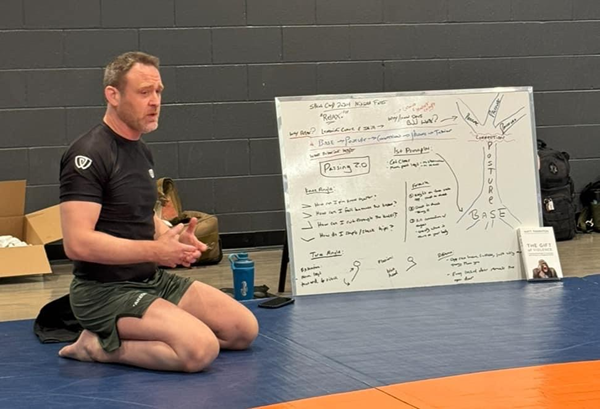

Earlier this year I had the pleasure of conducting a weekend seminar on guard passing at B.C. Jiu-Jitsu in Maryland (along with a number of private sessions), as well as teaching the topic at the SBG International Camp in Niagara Falls.

From Black Belt Chad Fazenbaker:

This weekend B.C. Jiu Jitsu hosted coach Stephen Whittier for a packed, two-day dual seminar on jiu jitsu and striking. Coach Whittier shared his expertise and learnings with us.

We are so grateful he traveled to Cumberland, MD to share some wicked instruction and formulas on passing guard and offense / defense for each body zone.

Thank you, Coach Whittier!

The topic of guard passing might mean many different things to different people when it comes to the “how.” But for me, it’s always the same: how to dramatically increase your effectiveness with the most efficient form of guard passing, which is bodyweight based passing.

For those of you familiar with The Pillars of Jiu-Jitsu: Guard Passing, you’ll know that this form of “pressure passing” is completely distinct from what most people mean by that term…

It is a first principles approach to maximizing your pressure using your weight, not your grips or arms.

It also happens to be the best form of guard passing for fighting (with strikes) and for pre-empting leg attack entries from the bottom player.

During the seminar, we zoomed in on some of the most common challenges students have (including black belts) in applying this style of passing.

These boil down to a few primary areas:

- Relaxation

There is a massive difference between Normal Jiu-Jitsu Relaxed and Optimally Relaxed.

Normal Jiu-Jitsu Relaxed means you’re not all tensed up, you can move smoothly, and you’re managing your energy so you’re not getting tired prematurely.

Optimally Relaxed is another level beyond this, where you’re simultaneously active with the one part of your body that’s touching the mat –– the balls of your feet –– but the rest of your body feels as close to a sand bag as possible. At the risk of the obvious, controlled breathing is a big part of this skill as well. - Correct weight placement

Hand in hand with greater levels of relaxation is the skill of specific placement of your weight based on how your opponent is orientated to you and how they are moving.

It’s astonishing the difference a couple of inches can make when it comes to your ability to pin a skilled opponent with just your weight (without relying on your arms) and your positional maintenance. With just small adjustments even larger opponents go from “that feels heavy but I can still move and work towards my escape” to “I can barely breathe, barely move, and don’t even want to move!” - Killing connection as early as possible

This isn’t about speed, it’s about immediacy. The earlier you can break your opponent’s primary connection to you at any given moment exactly where it occurs on your body, the harder it is for them to get their game going and the easier it is for you to advance. - Finding the open door

This is an important reframe to etch into your brain every time you are trying to pass and feel like the doorway you were trying to pass through is locked: instead of registering that moment as “it didn’t work”, instead register “thank you”… because every locked door reveals the open door.

Rather than teach the students exactly how to move in some rigid, paint by numbers sense, I instead provided them with a simple set of heuristics to find the opening to progress through the pass based on how far apart their opponent’s knees are and whether their opponent is extending or flexing their hips. - Patience

In some cases, as you become fluent in this style of passing you will blow through guards that previously gave you fits, and do it with much less effort than ever before, using just two or three movements.

But that’s not always the case. Some opponents will just have a style of play that matches up well against you or that you’re not used to yet. Your training partners will also begin to adapt to your game (which is a beautiful part of Jiu-Jitsu, since it forces ongoing adaptation and problem solving).

The goal isn’t how fast you can pass, it’s how efficiently. Here’s another reframe: it’s okay for your opponent to be able to do some of the things they want to do with their guard. Obviously we’re trying not to get submitted or swept (although that’s part of the learning process), but it’s okay for them to be able to have some “success” creating space and moving on bottom as long as they are expending more energy than you are. When that happens, their “energy bar” will eventually dwindle and you will pass, which also means that they will be depleted by the time you get to a dominant position –– where you can apply even more crippling body weight!

To check out more about this rare first principles approach, visit my instructional library here.